Reason, Rationalisation, Courage and Fear

This process is not about demonstrating why our assumptions are correct. Instead it is about challenging those assumptions.

“You are now armed and dangerous” Bill Dettmer said to us, his Logical Thinking Process students, at the end of his training course in Paris a few years ago.

We had spent six days getting trained in applying rigorous logic to analyse situations, uncover deep-seated root causes behind problems, solve difficult conflicts and map out sound future plans. Armed, for sure, but why dangerous?

The Logical Thinking Process is based on logic. We construct often large and complicated analyses of cause-effect relationships between events and decisions to identify what lies behind the problems we experience or what is needed to achieve a desired outcome. The diagrams themselves are both a method of analysis and its end result, and that way they also serve as a powerful tool to explain how we have arrived at the conclusion. And as an explanation tool, the analysis may also be used as a persuasion tool.

While most of us have the capacity for logical thinking, we also tend to avoid it. Too often, when presented with a complex analysis, as long as the logic looks sound and the conclusion fits with our own preconceived ideas, we tend to take it at face value instead of challenging the assumptions.

Even though a logical analysis diagram can be a great way of communicating the rationale behind a conclusion, this is not its primary purpose. Logical cause-effect diagrams are first and foremost intended as analysis tools, not presentation tools. In the end it is the process of building the analysis that matters.

This process is not about demonstrating why our assumptions are correct. Instead it is about challenging those assumptions. If we fail at this, we are likely to end up with wrong conclusions or wrong decisions, no matter how clever or how beautiful the logic may look on the surface.

Logic is a double-edged sword. When correctly used, it helps us cut through the tangle of complexity and illusions, clearing the way toward the inherent simplicity of even the most complicated system. When incorrectly used, it may further entangle us in the undergrowth of false assumptions, lead us away from clear headed honest reasoning where we challenge our assumptions, and into rationalising them. This is why someone equipped with the powerful weapon that logic is, is both armed and dangerous.

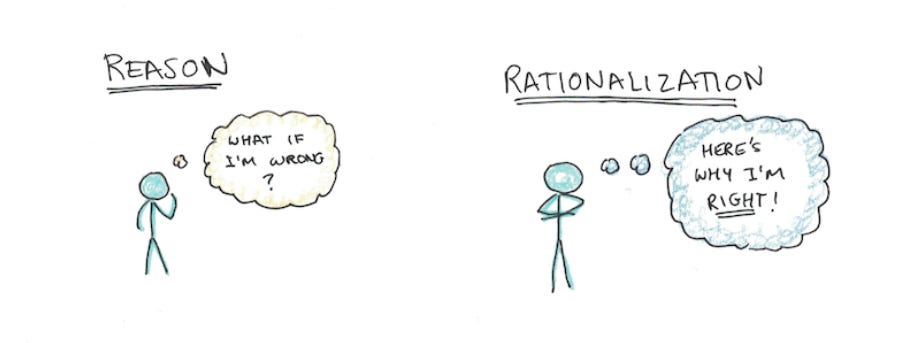

According to the dictionary, reasoning is “the drawing of inferences or conclusions through the use of reason.” Rationalising on the other hand is “to bring [something] into accord with reason or cause something to seem reasonable.”

In his seminal book Propagandes, French sociologist Jaques Ellul discusses the relationship between propaganda and rationalisation and how the propagandee, the person who has succumbed to propaganda, goes on to rationalise even the most atrocious actions or illogical beliefs based on it. “To the extent that man needs justifications, propaganda provides them” Ellul says: “But whereas his ordinary justifications are fragile … those furnished by propaganda are irrefutable and solid … Such an individual will have rationalisations not only for past actions, but for the future as well.”

This way, propaganda prevents the individual from thinking; from reasoning, but prompts him to toward rationalising. The propagandee fears everything that might challenge the beliefs instilled in him by the propaganda, and rationalisation is the defense against those challenges.

The result of propaganda is a paradigm that isn’t questioned. But propaganda is not a necessary condition for such a paradigm. As David Updegrove explains in his book Breakthrough to Clear Thinking and Innovation, established paradigms are usually very hard to break and before they do people go to great lengths to explain, to rationalise the inconsistencies inherent in them.

The key to a meaningful life is clear thinking Updegrove says, quoting Dr. Eli Goldratt. We are all capable of thinking clearly, but we fear the consequences it may have. Goldratt talks about four categories of fear, fear of complex systems, fear of the unknown, fear of conflict and fear of losing something we possess. But there is a fifth fear, Updegrove argues, and this is the fear of inciting a holy war with the system; challenging assumptions held by everyone else, ending up being reviled as a heretic. Dealing with this final category of fear is not easy. It is probably the single most important reason faulty paradigms can last for centuries.

While there are practical methods for dealing with each of those categories of fear, to successfully do so we need the stamina to follow through ideas to successful implementation, and for this courage is an essential component. To overcome the fifth category of fear, we need the courage to face inconsistencies, Updegrove says. He continues:

“One reason that some scientific paradigms are so hard to overturn is that their adherents often stop exercising the scientific method. They might in fact recognize inconsistencies between theory and evidence but rather than challenging (God forbid scrapping) the core theory they often either ignore the inconsistencies as irrelevant or build (sometimes gymnastic) secondary theories upon the original to account for the discrepancies or to fill in the “gaps”.”

What Updegrove describes here is rationalising, justifying, explaining away inconsistencies, instead of approaching them based on clear thinking. True reasoning is the opposite of rationalising, and to overcome the temptation of rationalising we need courage, the opposite of fear.

The purpose of logical analysis is to come to the correct conclusions by means of rigorous reasoning. It takes time and effort to learn to do it, but the time and effort is not the biggest obstacle. The biggest obstacle is fear. Instead of rationalising to convince others of a presupposed conclusion, true reasoning is all about challenging every factual claim, every assumption, every cause-effect connection. That includes being prepared to challenge our own deeply held beliefs. To do so we must overcome our fear. And to overcome our fear we need the courage to choose reasoning rather than rationalisation.

I find the issue of reasoning and rationalizing interesting. In a LTP analysis, we need to try reasoning and exposing all the claims while attempting to uncover the faulty assumptions.

This extends to science, and you mentioned the scientific method that utilizes cause-and-effect reasoning applied to theories. When a theory is developed, it should explain the facts, practical observations, and reality. If it fails to do so, two things can happen. Either the theory is upgraded, or if it fails outright, we should change or replace it.

However, in many cases, as Updegrove said, people prefer to ignore the inconsistencies and create alternative theories rather than challenge the wrong assumptions. An example of this is seen with Covid-19 vaccines, where people chose not to challenge the not-so-well-founded studies during vaccine development.

Another example that I'm becoming increasingly uncomfortable with is the hysterical behavior surrounding Climate Change. An implicit theory here states that the climate is changing (which is an oxymoron, as it has been changing for millions of years). The focal point is the supposedly "indisputable" connection between Climate Change and CO2 levels, assuming CO2 is the primary factor explaining climate. This assertion suggests that Climate Change is anthropogenic truth, caused by human emissions, and that our behavior should revolve around achieving net-zero variations or no CO2 emissions. This, in turn, would lower Earth's temperature (effect) and save the planet (the "glorious" effect).

The truth is, nobody really knows because we're dealing with a complex system of systems (Climate) with many variables and considerable complexity. Is it reasonable for me, or rather for a scientist, to be ostracized by their community and labeled a denier if they detect inconsistencies in this reasoning?

Climate Change is indeed an illustrative example of the reasoning and rationalization debate you mentioned. Its significance lies in the impact it has on our lives, not the climate itself, but the policies aimed at achieving Net Zero, even though many scientists question the necessity of Net Zero for any purpose!"

In the background to the issues discussed here are worldviews. As the West drifts from modern ideologies (derived from the Enlightenment) towards the postmodern worldview, this affects many things. The Enlightenment worldview was largely a reaction to the Judeo-Christian worldview and though it rejected the Judeo-Christian sacred text, the Bible, it still accepted the Judeo-Christian concept of Truth, yet placing this concept in Science (note the capital S...). Postmodernism is also a (more extreme) reaction to the Judeo-Christian worldview, rejecting even the Enlightenment concept of Truth. As a result, Science as Truth goes out the window... All that is left is the individual’s subjective feelings. This is a huge factor in the transgender debate where powerful social institutions back the concept that “feelings” trump biological facts. Just a few generations ago, such assertions could have landed you in a rubber-padded room... Richard Dawkins is a rare holdout to Modern/ Enlightenment thinking in his rejection of transgender ideology. While I don’t accept his worldview, I admire his courage to go against the current. Somewhat like that 1930’s era photo of a Nazi rally with everyone in the crowd raising their arm in the Nazi salute, except one man...

All of which takes us back to the temptation to rationalization. As you point out Thorsteinn, in ordinary life such temptations are unavoidable, but can be dealt with if individuals or social institutions care about Truth. One manifestation of this intellectual duty in science is caring about FACTS. As Postmodernism grows in influence, caring about facts becomes a secondary (or tertiary) issue... A number of years ago, reflecting on the possible repercussions of postmodern thought the British anthropologist Ernest Gellner observed:

"Quite probably, the break-through to the scientific miracle was only possible because some men were passionately, sincerely, whole-heartedly concerned with Truth. Will such passion survive the habit of granting oneself different kinds of truth according to the day of the week ?"

p. 93 in GELLNER, Ernst (1992/1999) Postmodernism, Reason and Religion.

If reason and logic are no more than arbitrary cultural conventions (as postmoderns assert), such a statement brings into question the whole concept of the university, a haven for universal knowledge, which is, ironically, typically postmoderns favourite refuge.